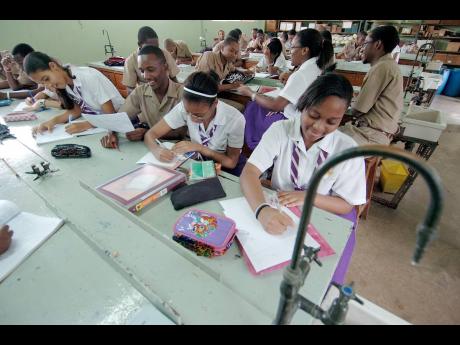

At the end of enslavement, most Africans on plantations in the Caribbean and North and South America were illiterate. Europeans used slave codes to make it a criminal offence for Africans to acquire this skill. This ensured that Africans would be psycho-socially crippled and dependent on Europeans for self and social definition.

In this way, education was weaponised as a tool of domination and exclusion. The legacies of a racialised education system plus insufficient access for those most in need are enduring problems. Advocates for a decolonised education system have long been struggling to remove such barriers to success. People like Dr Anna Julia Heywood Cooper ( A Voice from the South); Dr Carter. G. Woodson ( The Mis-Education of the Negro); and our own Marcus Garvey ( The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey) are among stellar educators who designed charters for emancipation from mental slavery as alternative methods for intellectual progress for the African majority class.

Although education is a gateway to upward social mobility, Jamaica remains mired in a Eurocentric approach to the form and content of the pedagogical product. This is a challenge to the crafting of frameworks or learning that facilitate self-realisation and cohesive national development. Case in point is the Government of Jamaica’s (GoJ’s) clumsy communication of an immediate shift to an apparently mandatory seven-year high school schedule. A sensitive leadership would invest more effort and time in persuading the beneficiaries of the reasonableness of taking this pathway (to use the unfortunate brand) at this time.

INSENSITIVE

The choice to use the traditional top-down approach to dictate to a digitised generation of students is insensitive of the Convention on the Rights of the Child’s (CRC’s) stipulation that children must know about decisions that affect their lives. This fundamental right is in recognition that even if caregivers inside and outside of the household are acting in the best interests of their wards, they are obliged to consult said children and ensure that their participation in the decision-making process is facilitated and encouraged.

That consultation approach was missing from the recent Nicodemus policy, which stipulates that fifth-form graduation ceremonies would be cancelled this year to make way for the onset of a mandatory seven-year high-school engagement model. The government announcement appeared as another top-down decision, which was unplanned and ideologically unconvincing. Some students erupted in consternation as their exit strategies from high school do not mandate attendance at sixth-form level.

At first byte, the news sounded as if it would now be compulsory for students to attend school for seven and not five years. On second read, however, this news is not that novel. It is a conversation that has been flagged for some time in recognition of the reality that more and more students are graduating into a sterile socio-economic environment. The paucity of “work” in the public space has prompted the GOJ in the past to promote initiatives to protect children from the hostile public-sector environment for as long as possible. Delaying students’ entry into the world of work acknowledges that the employment environment is hostile to school leavers not only from high school , but also tertiary institutions.

Beyond paucity of employment on the job market, many students are not work-ready when they opt to leave at the end of fifth form (grade 11). The two years spent at sixth- form level (grades 12-13) are designed to build out personal development potential, improve work eligibility and qualifications, and hone young intellects for tertiary-level advancement. For those who accept the option of the seven-year model, achieving an associate Degree at the end of the period is a good thing even if the packaging of this prize is problematic.

All these intentions are all very well and good. But it was the timing and style of the announcement that galled those who railed and are still protesting. Their angst has to do with the fact that the matriculation requirements have not changed for tertiary institutions like teachers’ colleges, the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts, Northern Caribbean University, and come to think of it, also The University of the West Indies (The UWI), which admits part-time entrants on the strength of Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) passes. CXC conventions have also not been changed in other Caribbean countries. This decision to suddenly remodel the school-leaving arrangement could be seen as what Dr Eric Williams meant when he called Jamaica’s pulling out of the Caribbean Federation a case of 1 from 10 leaves Zero.

WHITE ELEPHANT POLITICS

The GoJ’s Sixth Form Pathways Programme is based on the 11-year old Career Advancement Programme (CAP), the high-rolling post-secondary school-enhancement model, which offered 40,000 CAPE students subsidised education opportunities, and some 63,000 students were enabled to resit CSEC subjects like mathematics and English; improve personal development and technical skills, and bolster success possibilities at the tertiary level.

This was initiated in 2010, and just over a decade later, this well-meaning white elephant is being hailed as the baseline for the normalisation of this approach. What were the CAP outcomes? What are the success stories? Where is the Tracer Study to countervail the claim that the certification did not translate to job and schooling successes? What value did the investment of over eight hundred million dollars have on young people’s ability to get jobs or enrol in tertiary institutions? Will that substantial material support be replicated in the new normal of an extended school schedule as happened with the CAP experiment?

Concerns about form and content of school engagement are more relevant now than ever as the nation hovers in the twilight zone between remote and face-to face options. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Caribbean Policy Research Institute (CaPRI), the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the disruption of school engagement for 600,000 students, 25,000 educators and numerous parents, service providers, and other significant dependants on the system (see https://www.capricaribbean.org/discussion/effects-covid-19-education-sector).

The jury is still out on the number of children who have disappeared from the system due to lack of access to hardware and connectivity and their inability to pivot to meet the unprecedented demands of the new mechanisms of pedagogical engagement. It is a time for the carrot not the stick.

– Dr Imani Tafari-Ama is a research fellow at The Institute for Gender and Development Studies, Regional Coordinating Office (IGDS-RCO), at The University of the West Indies. She is the author of ‘Blood, Bullets and Bodies: Sexual Politics Below Jamaica’s Poverty Line’ and ‘Up for Air: This Half Has Never Been Told’, a historical novel on the Tivoli Gardens incursion. Send feedback to [email protected].